Pavla Kaňková

+420 771 297 711

29. 04. 2025

A great expert doesn’t automatically make a great leader. So, how can we reduce the risk of ruining a talented individual or a functioning team through a poorly chosen promotion? Outstanding performance in a specialist role doesn’t guarantee success in a managerial one, yet many companies still promote people “based on merit”. Why does this sometimes work—and why does it so often not? Marta Fabiánová’s article for HR News explores exactly that.

The saying “Give a fool a position of power” is probably familiar to everyone, and many of us have seen it firsthand. But in reality, it’s much more common to encounter something subtler: leadership roles given to the most capable, reliable, successful experts. Sometimes this works out perfectly. Other times, to put it politely, it ends in disaster.

One recent case keeps coming to mind: after conducting a large employee survey, we discovered that one of the main issues was that many managers weren’t actually fulfilling the role of leaders. They didn’t act like leaders, they didn’t feel like leaders, and they weren’t perceived as leaders—either by top management (who saw them as lacking authority) or by their subordinates. In fact, their teams often saw them more as a shield against “evil” management, and were almost relieved that information didn’t really pass through them.

These “non-leader” leaders were often asked to take on the managerial role without really wanting it. Many said yes out of fear, thinking, “If not me, then who?” Yet in reality, they lacked the qualities necessary for the role—or, more accurately, no one ever checked whether they had them.

For someone to excel in a particular role, their aptitudes, abilities, skills, and talents must match the demands of that role, as well as the company’s culture. In practice, occupational psychodiagnostic tools help identify this match.

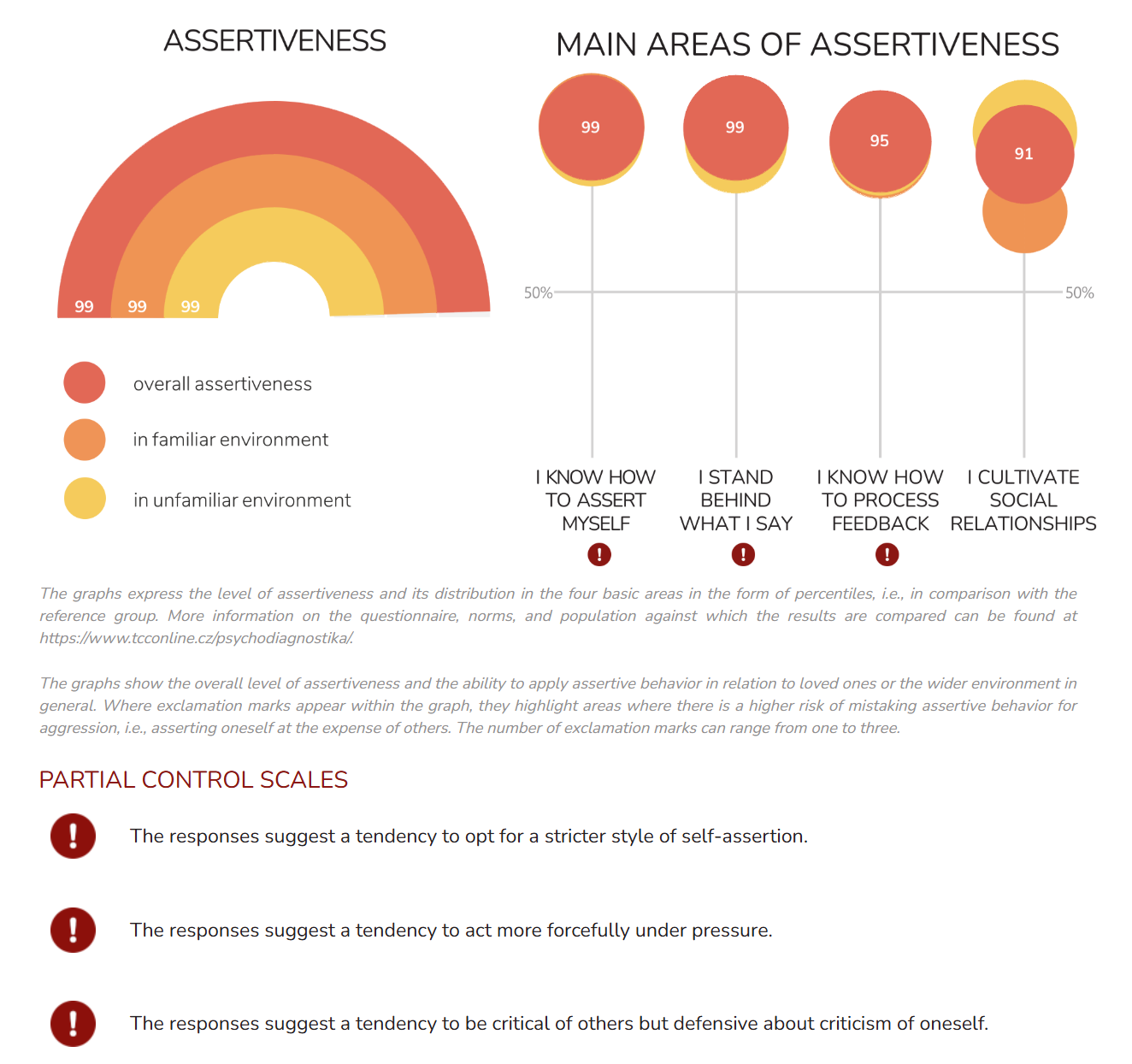

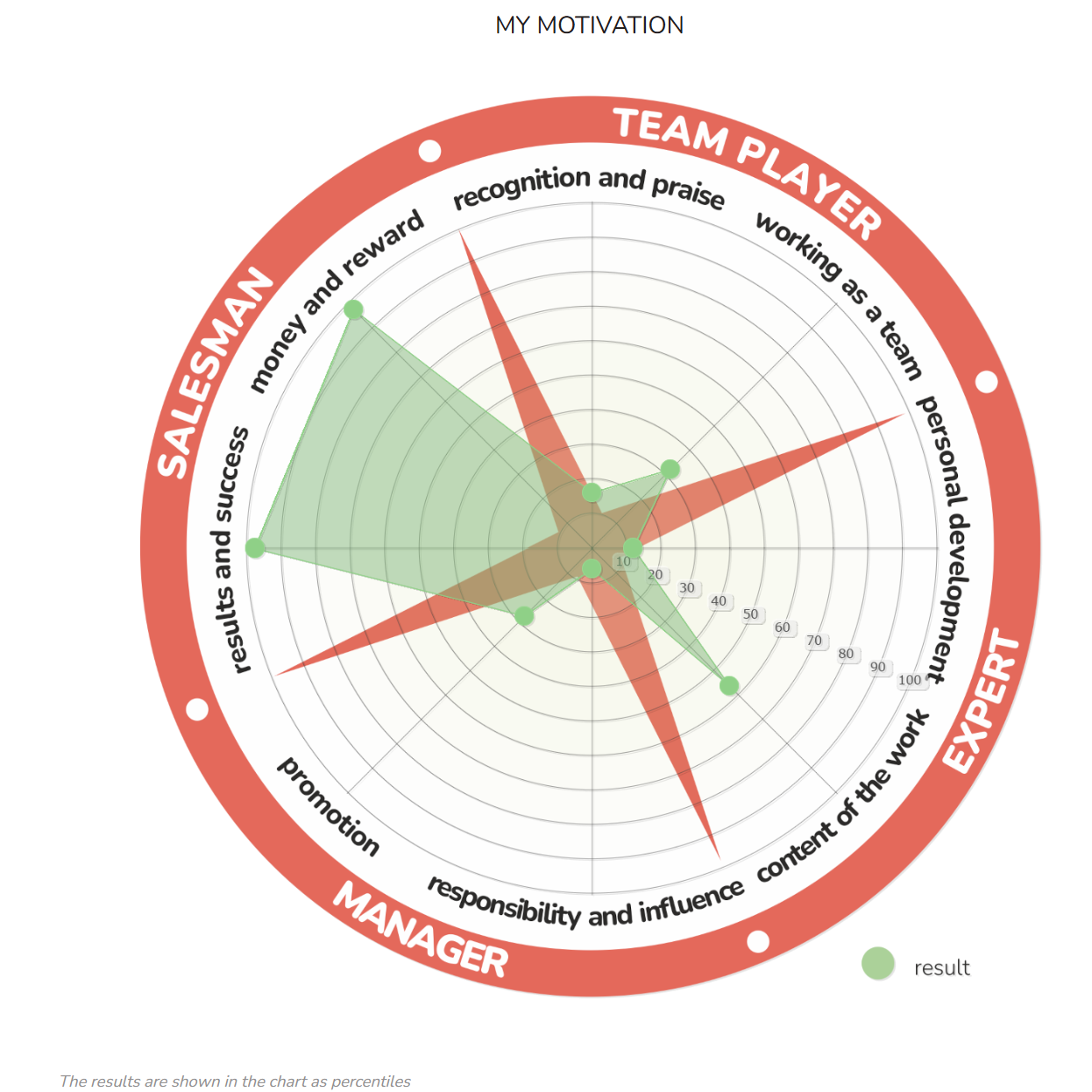

I recall a client where we used occupational psychodiagnostics to recruit talented salespeople—“hunters” whose main job was to acquire and persuade clients. The client was considering promoting one of their most successful hunters to a team manager role. Psychodiagnostic charts clearly showed how perfectly this salesperson fit their current role—both in motivational profile and an exceptionally strong assertiveness skill set.

Source: Chart from the output report of the Communication Style – Assertiveness Questionnaire (WORK), TCC online

Source: Chart from the output report of the Career Compass Questionnaire, TCC online

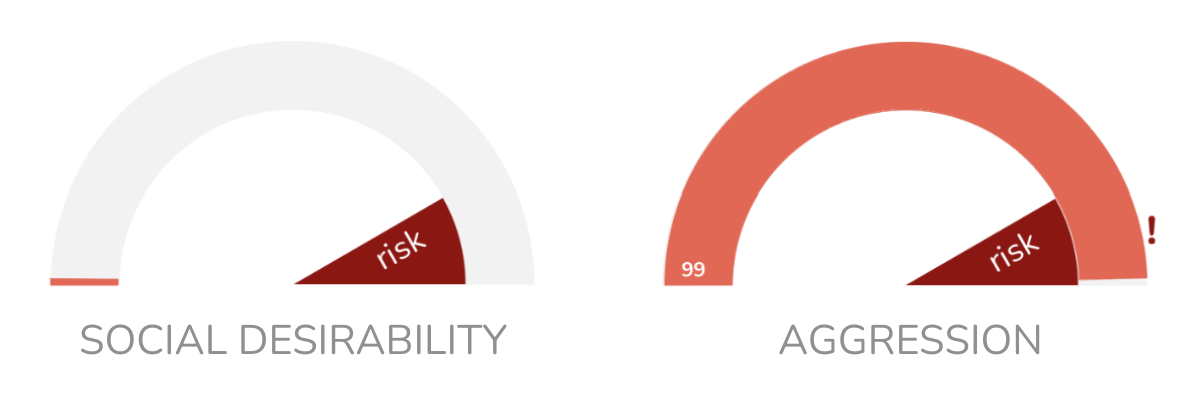

Thanks to the control scale, which detects tendencies toward aggressive behavior (such as using pressure tactics or raising one’s voice), we could also see how risky it would be to place this person in a managerial role. Aggressive tendencies can still be somewhat managed in a sales role, but in a leadership position, they could quickly destabilize the team. Several candidates had similarly risky profiles. In the end, the client wisely decided to keep their best hunters where they excelled and looked for a team leader elsewhere.

Source: Chart from the output report of the Communication Style – Assertiveness (WORK) – Control Scales Result, TCC online

At another client, during an internal assessment center, we also mapped people’s motivation for a managerial role. I remember one participant admitting that he saw management purely as a way to earn a higher salary—he felt it was a necessary next step in his career. He was an excellent specialist and a great team player, capable of developing managerial skills and taking a responsible approach to the role, but he didn’t love leadership. I don’t know how his story continued, but it’s quite possible that the client, by gaining a solid manager, lost an exceptional expert.

Similarly, we’re currently helping a large multinational company address a situation where all branch managers were promoted internally. They were all talented, successful, and motivated. Yet once in management, things started falling apart. It became clear that integrating occupational psychodiagnostics into the selection process was the right move. By analyzing the profiles of current managers, we could define an optimal profile for the role—one that genuinely matches the demands of leadership and correlates with strong outcomes like low turnover and high branch performance.

Conducting internal recruitment carefully greatly increases the chance that only specialists whose personalities, skills, and motivations truly fit a managerial role are promoted.

If we want to meaningfully promote specialists into leadership positions, we need to be clear on a few points:

A promotion should not simply be a reward for past performance. It must be a thoughtful decision based on genuine leadership potential. If we want to build strong management teams without losing our experts, we have to look beyond spreadsheets and years of service, ideally using validated tools and open dialogue.

16. 09. 2025

External vs. internal comparisons, averages vs. percentiles, trends vs. absolute values — a benchmark can be a good servant but a bad...

14. 08. 2025

Corporate culture is not about mottos in hallways or colorful presentations at meetings. It shows in everyday situations: in communication,...